June 30, 2020

Review: Queer Filmmaker David France's "Welcome to Chechnya" Should Be Compulsory Viewing for the LGBT Community and Beyond

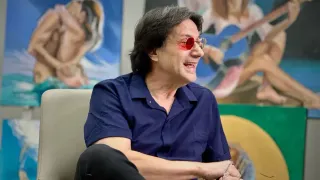

Roger Walker-Dack READ TIME: 4 MIN.

The third documentary from former Newsweek investigative journalist turned filmmaker David France, "Welcome to Chechnya," is one of the most harrowing depictions of contemporary LGBTQ life that we will ever have to sit through. Fortunately, France and his team are skilled enough to tell the stories with such heartfelt compassion that we don't feel like voyeurs but rather witnesses to a scenario that should shock us into some sort of action.

"Welcome to Chechnya" may appear to be a documentary thriller, but it starts off with a sobering statement:

"It happened under Stalin and Hitler. A whole section of the public were identified for extermination without charges or trials. This time it's not Jews but homosexuals."

This quote is from Olga Baranova, the Director of Moscow Community Centre for LGBT+ Initiatives, who is one of the leaders of the underground movement to help Chechen's gays escape with their lives.

Chechnya is a remote southern Republic of the former USSR and is run by ruthless despot Raman Kadyrov, who was appointed president by Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Whilst Kadyrov outright denies the persecution of gays – and even claims there are no gays in Chechnya – in 2017, it was he who began this most pernicious crackdown. Every man (or woman) who was arrested just for being gay was brutally tortured until they gave the authorities details of at least 10 of their gay friends or contacts. Those people, in turn, were then arrested and given the same treatment, which resulted in the police having the identities of a fair proportion of the local LGBTQ community.

The means of torture went way beyond anything the Americans did to prisoners in Iraq; many people died in custody, and their bodies dumped without a trace. The authorities in this Muslim state were only helped by attitudes from the local "straight" population; "honor killings" of gays by their own family members are reportedly not uncommon in Chechnya.

It was, says David Isteev, the Crisis Response Coordinator of The Russian LGBT Network, something that "only could be washed away by blood."

Despite the personal risks, Isteev and his colleagues plotted and planned rescuing as many gay men and women trapped in Chechnya that they could. It took a great deal of guts, an immense amount of money, and safe houses throughout Europe. They also ran a shelter in a Moscow suburb as a halfway house for those hoping to get travel permits to Canada or Europe.

In the film's final credits we learn that in the first two years of the Chechnya purge, the underground network resettled 151 people. Fifty-five of those were accepted by Canada. The U.S. has accepted NONE.

France focuses on the story of "Grisha," a Russian man who was visiting Chechnya when he got caught in the roundup and was very badly tortured. However, as he was not a local, the police let him go, which in the end they would regret. Once they realized that Grisha was free to tell his story, they came to Moscow to hunt him down; unable to find him, they threatened his entire family. With Grisha tucked away temporarily in the shelter and reunited with his boyfriend of 10 years, the Rescue Coordinators found a safe house for his entire family.

They were all then whisked away to an unnamed European country and a new life, but were still warned that they would never be 100% safe, as the long arm of Kadyrov's men could still discover them even there.

Not only did everyone being rescued and passing through Moscow adopt a fake name for security's sake, but France also used a brand new technology that digitizes all the faces of those appearing in the film beyond recognition. It was only when Grisha made the remarkably brave decision to appear before a Russian panel on torture back in Moscow, and also sue the government, that his real face and name came to light: Maxim Lapunov.

Lapunov is the first and, so far, only gay man to come forward publicly about being tortured during the purge. The Panel was "sympathetic," but the court refused to hear the case. It's fair to say that the viewer worries as much as Lapunov's family that his bravery will end up costing him his life.

Now he is taking the case to the European Court of Human Rights, which may prove powerless to get Chechnya to change its ways, but at the very least it has brought the matter into the public arena so other countries can make their own choices on how to deal with the brutal regime.

By the end of the film, Baranova is also in danger and needs to be rescued herself. How she and David Isteev risk so much personally to help save the lives of total strangers reminds us of how much good there still is in the world.

France's first two movies looked back at crucial points in queer history. His Oscar-nominated "How to Survive A Plague" is a seminal movie on the AIDS epidemic. More recently, France took a look at another courageous LGBTQ figure with the "The Death & Life of Marsha P. Johnson," about the transgender civil rights activist. France's finely tuned powers of observation ensure this latest film will be remembered as recording history in the making.

No matter how painful this devastating story may be, it should be compulsory viewing for the LGBT community and beyond, helping spread awareness of the atrocities in Chechnya and hopefully resulting in more people taking action to save innocent lives.