November 14, 2023

53 Years Later, An Unsung Queer Director's Film Finally Comes to America

C.J. Prince READ TIME: 6 MIN.

Over five decades after its premiere in 1970, French filmmaker Paul Vecchiali's "The Strangler" has made its way to America. Described as a French giallo film, a horror subgenre of murder mysteries made popular by Italian filmmakers like Mario Bava and Dario Argento, Vecchiali's third feature was his largest scale project at the time, an early work within a prolific career that saw him making films up to his death in January 2023 at the age of 92. Altered Innocence, an independent distributor with a focus on international LGBTQ+ works, will release a 2K restoration of "The Strangler" this month in New York City, with more screenings planned across the U.S.

Set in Paris, the film follows Émile (Jacques Perrin), a serial killer who roams the streets preying on depressed, lonely women. A flashback shows a young Émile observing a man strangle a woman to death with a scarf, a formative experience that becomes his signature method of dispatching his victims. Several people orbit around Émile; Simon (Julien Guiomar), an inspector investigating the murders, whose fascination with the case pushes him into ethically questionable territory; Anna (Eva Simonet), a woman who pursues Simon and Émile believing she will be a future victim; and a thief (Paul Barge) who trails Émile so he can rob the bodies of the victims, which infuriates Émile as the media believe he's the one doing the robberies.

"I'd say 'The Strangler' is [Vecchiali's] first masterpiece, his first film where the viewer's sense of him is undeniable," Bingham Bryant, who co-programmed "The Strangler" along with other films Vecchiali directed and produced for New York's Metrograph cinema, told EDGE. Even now, with countless crime films made since "The Strangler" premiered, the film stands out as wholly original thanks to Vecchiali's screenplay and direction. The scenes where Émile murders his victims play out as quiet and intimate, the depressed women he targets expressing a sense of relief from their misery as he wraps his white scarf around their necks. By the film's halfway point, Simon finds Émile but doesn't arrest him. Instead, he strikes up a conversation and lets him go, with the demand that he stop the killings for only a few days.

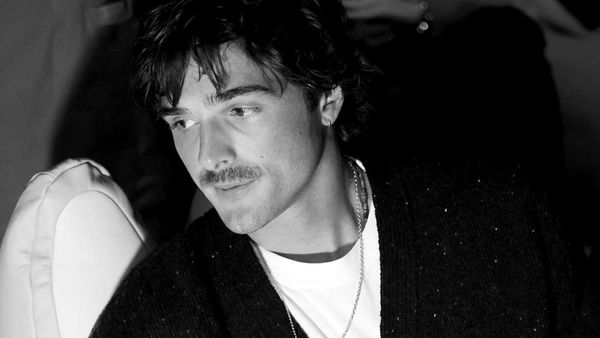

Source: Courtesy of Altered Innocence

Characters rarely behave in a way that could be described as realistic, yet their actions never come across as unnatural in the world of "The Strangler." With these subversions of the genre, Vecchiali foregrounds existential themes around desire, death, and the allure of danger. This collapses the distance and escapism of the serial killer story, which allows Vecchiali to open the film up to digressions and unpredictable turns: a musical number at a nautical-themed bar, a morbid sequence of Émile imagining the streets of Paris run amok with violence, and a group of sex workers who band together when Émile attempts to kill one of their own. Rather than take the familiar route of a murder mystery, or dwell on the salacious elements, Vecchiali paves his own, roundabout path to examine the human condition.

A writer who also wrote criticism for "Cahiers du Cinéma" (the same place where filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Éric Rohmer started), Vecchiali began making films in the 1960s. He continued working behind the camera over the decades, while producing other works including Chantal Akerman's "Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles," which was declared the greatest film of all time in 2022. After the success of his 1974 feature "Femmes Femmes," which Pier Paolo Pasolini loved so much he remade a scene in one of his own films, Vecchiali created Diagonale, a production company that made dozens of low budget films from the '70s to the '90s, including features and shorts by queer filmmakers.

Upon learning about Vecchiali, a natural question arises: How did someone so prolific and influential remain obscure throughout his career? Bryant explains that this was likely intentional. "Diagonale was a haven for modest, small films by design, built not to accrue acclaim and resources but to mark out and enclose a stable and sustainable filmmaking ecosystem for himself and the filmmakers he loved." Relying on government funding, Vecchiali and Diagonale's films remained low budget and sidestepped avenues like international film festivals and distribution for practical reasons. "Vecchiali realized that these [networks] couldn't be depended upon to consistently support the kinds of films Diagonale was making, so he turned away from them... the films remained obscure, but Vecchiali had his system worked out so that this didn't matter much, at least for a time."

That time came to an end around the late 1980s, when Diagonale was unable to continue under its business model. Vecchiali's output as a director slowed down in the 1990s before he returned in the 2000s, during which he maintained a consistent output until his death. His films, as well as the others made through Diagonale, seized upon their status in the margins to make defiant, queer works. One of the most notable of Vecchiali's features is 1988's "Once More," a drama about a husband who leaves his wife and falls in love with another man. It's commonly cited as the first French feature to directly address the AIDS crisis within the homosexual community.

Of course, Vecchiali is too singular to have "Once More" reduced to being no more than an AIDS movie. Set over a decade, each scene jumps ahead one year in time, and each of these "episodes" unfolds in a single take. There's a lot of artifice, and some moments take direct inspiration from stage productions, yet the elliptical storytelling flattens the major life events to give the film a cumulative, emotional impact (while AIDS plays a crucial role in the story, it's introduced late in the film and in the same matter-of-fact manner as the plot points before it).

Part of Vecchiali's strengths as a filmmaker were in his handling of queerness. While his films may have queer ideas and themes, they functioned as parts of a whole rather than make up the center. Bryant describes Vecchiali and Diagonale's films as "an immeasurably rich whole world unto themselves," with a focus on lives and sentiments rarely seen in cinema. "He knew he was often breaking taboos, codes of silence about subjects like AIDS or lesbian and gay subcultures, but I think he did this more because of an irrepressible need in his cinema to take people as they are, with all their contradictions, secrets, ambiguities, and particularity intact."

With "The Strangler," as well as recent restorations of other Vecchiali and Diagonale films, audiences will finally get a chance to discover this rich, obscure world for themselves.