December 28, 2015

Gay Marriage Fight Named Top Alabama News Story of 2015

READ TIME: 1 MIN.

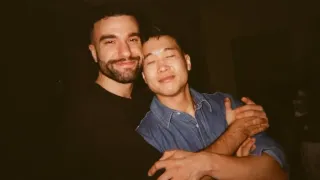

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Alabama's uneven response to court rulings allowing same-sex marriages is the top state news story of 2015 as selected by The Associated Press.

Gay marriage became a reality nationwide this year, but the issue took on special significance in Alabama as officials grappled with how to respond to court rulings allowing same-sex weddings.

Some counties complied with court decisions immediately and issued same-sex marriage licenses. Others delayed or quit issuing marriage licenses altogether, forcing both gay and straight couples to go elsewhere to get married.

More court battles are possible in 2016.

The release of author Harper Lee's second novel, "Go Set a Watchman," is the state's second-biggest news story of Alabama. The state budget crisis rounds out the top three.